Writer & policy consultant

- Fiction

- The Whirligig

“I do not know how long it will be before the car stops and the men inside it come for me. My story has run its course in any case. In the telling of it, I hope that some meaning can be found. It is too late for me, but it must mean something. It cannot end – I cannot end – for no purpose at all.”

The year is nineteen thirty-something and Anton Guebler is locked in the boot of a moving car, racing through the darkened streets of an unnamed city. He contemplates his inevitable and imminent death, picking through the course of his life, from the poor neighbourhood of his childhood to the office of the city’s charismatic and radical mayor.

"The mood is unmistakably tense —smoke-hazed rooms, uneasy political currents, and a constant sense that something is shifting just out of sight."

Reader reviewWhen Anton joined the mayor’s office as an adviser, he was full of optimism, intent on making the world a better place while also making his own mark upon it. He manages to hang onto his idealism even as events take a darker turn. Only once he is forced to choose, between loyalty to the mayor and betraying the people he loves, do the doubts creep in, too late. But was it all for nothing? And could he have defied his fate?

“Harvey weaves a magnetic tale of human hope and betrayal with depth and insight. A triumph.”

James Silvester, author of Escape to PerditionA thrilling story of politics and power, of loyalty and betrayal, and of the good intentions that pave the road to hell.

“Harvey’s beautiful prose explores the personal side of politics and the flawed people who pursue it.”

Emma Burnell, political journalist and playwrightThe Whirligig is published by February Books and is available from all reputable booksellers (and some disreputable ones).

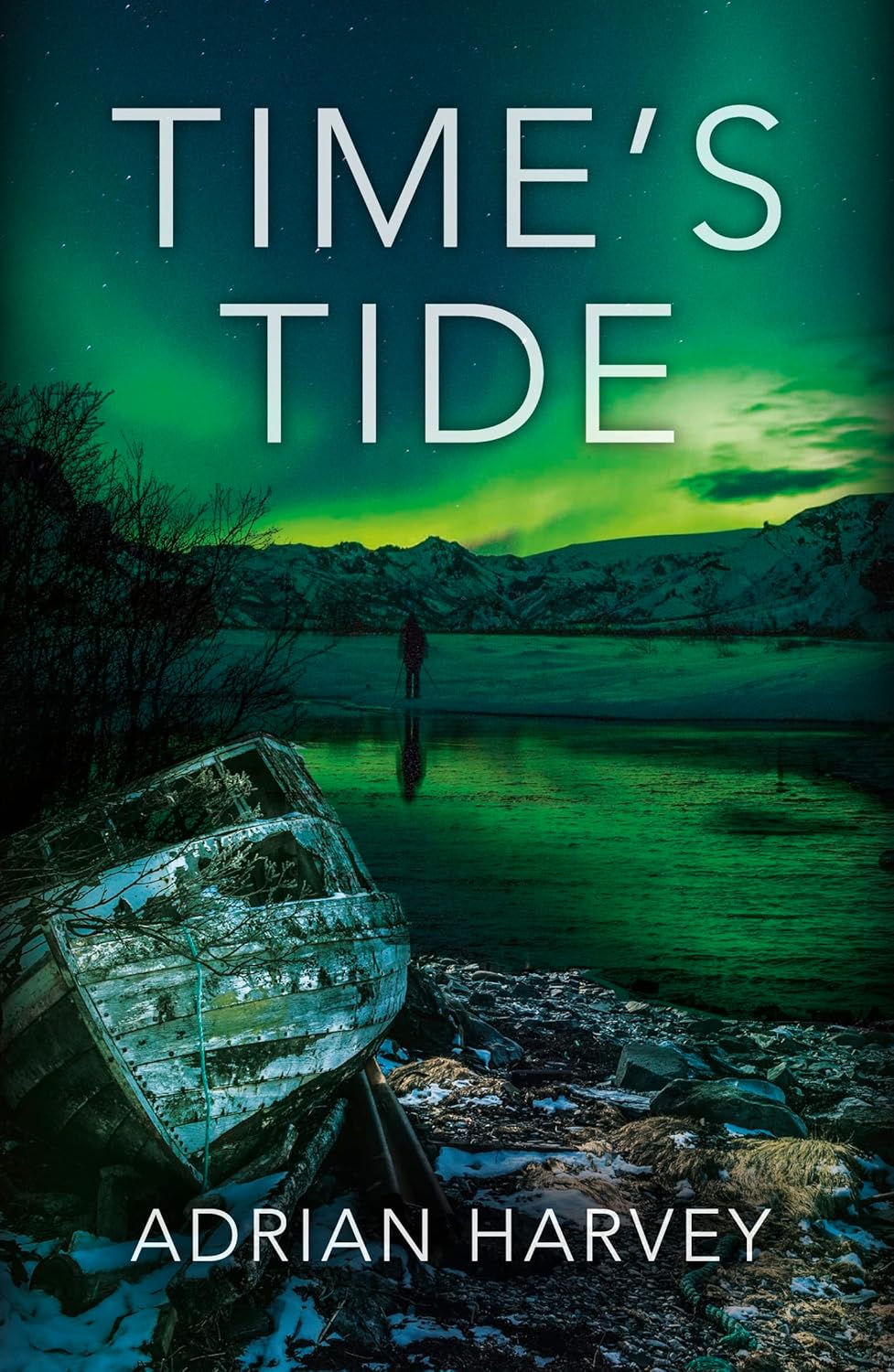

- Time's Tide

“On a morning like this, it was hard to recall the dark, deep days of winter, the ice and wind and hunger; the months when inaction and confinement, the empty waiting between scant meals, had gnawed through the soul as much as the stomach.”

A father and son struggle to overcome the distance between them. Each is drawn irresistibly to an unforgiving landscape, one that has been the scene of tragedy and loss. The son’s return to the northern shore he abandoned as a young man promises the chance to heal the rift. But is it too late?

"A moving exploration of the relationship between fathers and sons, and how the passing of time does nothing to quell grief."

– CUB MagazineÁrni left his remote corner of Iceland as soon as he could, seeking opportunities beyond winter and fishing. Married to an English woman, he builds a life as a successful scientist but can never quite escape the pull of the West Fjords and the bleak landscape of his birth, nor shake the guilt he feels towards his distant father. When Eiríkur goes missing, he sets off to find him on the windswept spit of land lost in an angry ocean.

"The brooding sea and stark landscape are key characters in this time-hopping novel with an unexpected twist... The closer I got to the end, the more difficult it was to put down."

– Amazon reviewA story of loss, belonging and the silence between fathers and sons.

"From the beautiful rugged descriptions of landscape to the subtle and perceptive observations on relationships this is a powerful and gripping read. Beautiful and haunting."

– NB MagazineTime's Tide is published by Bloodhound Books and is available from Amazon.

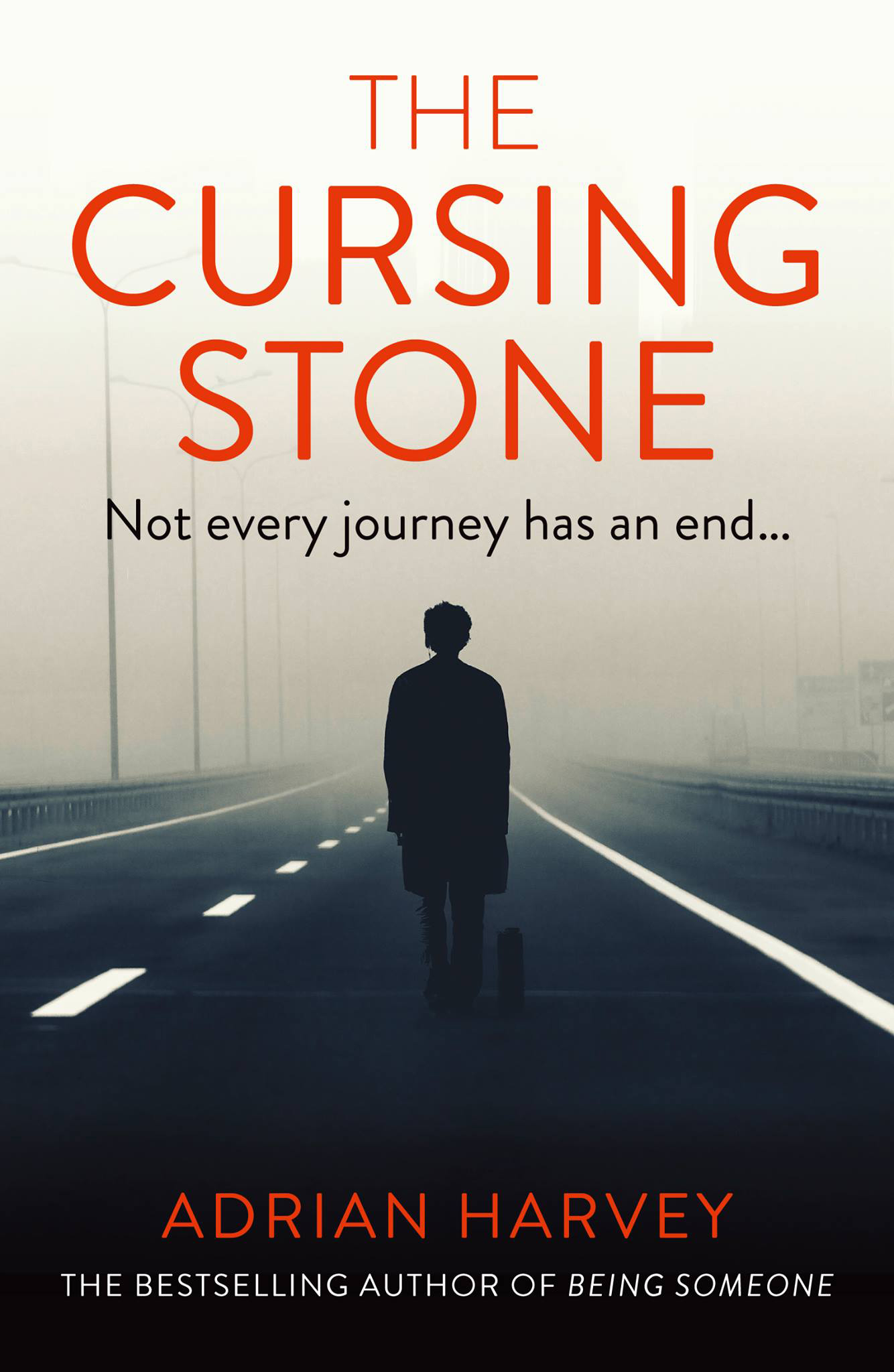

- The Cursing Stone

This image has a caption “Oh come now, Mr Buchanan. When one goes out into the world, one always ends up smelling of something or other.”

Fergus Buchanan has led a charmed life: a doting family, a loving sweetheart and the respect of his neighbours. All is as it should be and nothing stands between him and the limitless happiness that is his destiny. But then he is sent from his remote island to retrieve the cursing stone, and his adventures in the wild world beyond cause him to question everything he thought he knew. Succeed or fail, nothing will be the same again.

“a wonderfully charismatic story of family ties, loves lost and found, courage, duty and a long awaited revenge.”

– Amazon reviewThe Cursing Stone is published by Bloodhound Books. It is available from Amazon.

“The prose lingers over the landscape and the life of the people on it.”

– Strange Alliances review

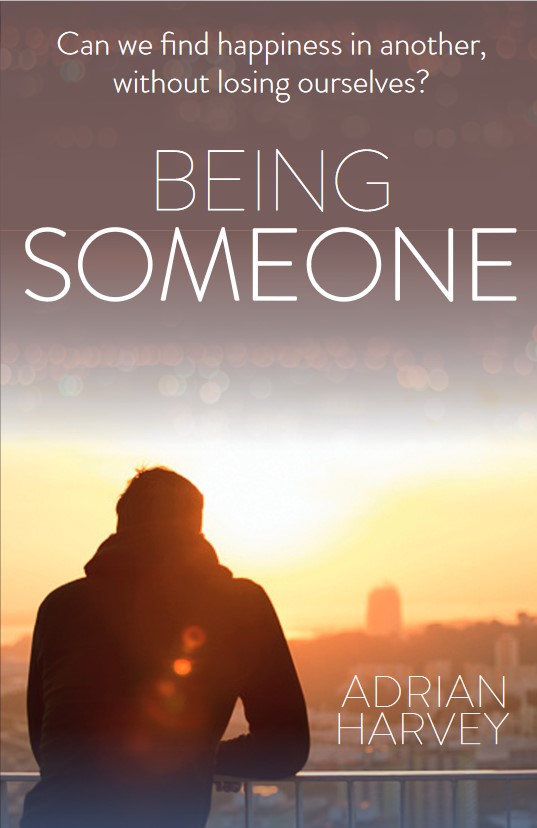

- Being Someone

James Townsend is not a bastard, he just can’t make decisions. At least not the right ones: about what he wants or who he is. The affair had seemed like a good decision but now that this too has crashed to failure, he has returned into his past in search of something to make sense of how he got here. At home, everyone else is just trying to find some meaning in the debris.

“the writing is absolutely beautiful; mature and with a deep understanding of how to construct characters, the writing is warm and inviting.”

– My Little Bookblog reviewYou can read some reviews at My Little Book Blog, Linda’s Book Bag, Trip Fiction and at The Bookbag, who also interviewed me. And you can read my guest blog on the inspiration for the novel at A Lover of Books. And, over the summer of 2015, Being Someone was selected for the WH Smith ‘Fresh Talent’ promotion, “showcasing the very best in new and emerging writing talent”; the book had a lovely new cover for the occasion and made it into the WHS chart. The launch event even made it into the Tatler...

Being Someone was my first novel and was originally published by Urbane Publications, and now is now with Bloodhound Books. It is available from Amazon

“lucid, engaging and emotionally intelligent, with a filmic quality borne of the narrative style and the profound sense of place”

– Amazon review

- Short Works

Most of my creative writing is focused on my novels, but other things slip out between the cracks. Occasionally I will post those things here: short stories like Fuse (a reflection on my home-town youth) and poems like Between (which I wrote as a reading for a wedding).

- Two

The yard was full of them. Milling about. Putting their noses into other people’s business. Into his business. Andy stared at them from the gate, watched them spread across the yard, looking into windows, looking under vehicles. The morning sunlight made their yellow jackets look sickly, made them look like cartoon characters, ridiculous. The hats were even more ridiculous. Like boobs. He remembered the playground joke, but it had been a long time and he had forgotten how to laugh; there was just bitterness in his mouth. Tits.

One of them, like the others but with a peaked cap, stood in the middle of the yard. He was pointing at things, yelling instructions to the others as they scurried about. He was the one in charge. Andy glowered at him for a little while, until the sharp rap of a gloved hand on the farmhouse door stilled the air. Even the crows shut up for a second. The two of them, by his front door, a short one peering in through the letter box, the taller one standing back to look up at the upstairs windows. Looking for him.

The taller one shouted his name and Andy very nearly shouted back. It would have been easy and it might have meant that he could get into his house sooner, put away the shopping before the milk turned. They were in his way. All this nonsense should just go away, let him get on with things. When he saw one of them start to try the latch on the barn, however, he stiffened. His knuckles whitened around the handle of the shopping bag.

The bag’s weight reasserted itself and the handle bit into him. He had bought a lot. The usual. Every other day, once he’d checked on the hens, he trudged down Holly Lane to the village to replenish his larder and pick up any other things that were needed. That morning had been much the same, save for his mood, which matched the brooding cloud that hung heavily over the eastern sky, pressing purple light onto the pastureland that had belonged to his parents. Until he had sold it, nearly ten years ago.

As always, he had ignored the church, which some might regard as pretty. He was intent only on getting into the Nisa. There was not much else in the village now, just the Nisa and the church. The pub had been turned into a house before he’d been able to drink there legally, and now the Rose and Crown was just a house name, picked out in white on a slab of slate beside the door. You’d never know it had been a pub otherwise, unless you’d lived in the village before.

The telephone box was still there, bright red on the triangle of green where the road split, but instead of a telephone the box now contained a defibrillator, whatever that was. Andy had ignored it as he walked across the grass to the shop. The dew still clung to it, and the brown leather of his shoes had become mottled with the damp.

The shop too was new. It had been across the road when he was a boy, in what was now another house, the Old Post Office. Then the Nisa had been built on the plot where the garage had been. Barry and Sons Motors. Andy had tried to remember any of the Barry boys from his school but there was no trace. Outside the shop door, he tried again to remember the building that had stood here for the first twenty years of his life, but that too was opaque. A void, an absence completely filled by the glass and bright colours of the Nisa. Andy had shaken his head. There was no point thinking about before. Better to deal with things as they were. Resolute, he walked into the shop.

Mr Elliot looked up from his phone at the sound of the door’s swish and the ‘bee-boo’ that accompanied it. He smiled his perennial smile and thought about that film with the robot. It was a comforting sound, in part because it was often the only voice he would hear for hours, but more because it meant a customer. Eight years he’d had this shop, ever since it had been built, and not one year had been comfortable, financially speaking. And that was mainly how Mr Elliot spoke these days. Financially. It drove his wife to distraction, he knew, but she had been the one to encourage him to take on the lease. It would be good for him to be his own boss, apparently, and she had been just as keen to be involved herself. She had rolled the words around her mouth like fine wine: small business people; entrepreneurs.

She’d lasted a couple of months before she stopped coming in to work with him, leaving him to manage stock, suppliers and customers all on his own, from 8am to 9pm, and eleven ‘til five on a Sunday. He hardly saw her now. He’d had an assistant for a while, but the finances didn’t stack up. So it was just him, the delivery drivers, a few customers and the robot. R2 something.

Bee boo.

He’d known it would be Andy. Andy tended to come in at the same time, two or three times a week. Mr Elliot suspected that Andy was as lonely as he was himself, but he’d never asked. Didn’t want to risk scaring off one of the too-few regulars. Most of the locals, the ones that had been born and raised in the village, they were chatty. They didn’t mind what they asked anyone, always getting into other people’s business. Not him. Mr Elliot had moved from the city, where people had more respect for boundaries, for other people’s privacy. Mrs Elliot’s idea of course. A better quality of life in the country, less hustle and bustle. Well, maybe if you weren’t stuck behind a till for 13 hours a day, you might feel differently.

He watched Andy picking his way along the aisles, selecting carefully the items that he placed in his basket. Andy was like him, Mr Elliot thought. He had respect for boundaries, despite being a native born villager. While some of his regulars, and not just the women, would spend more time gossiping than they did money, Andy was always brief. He wasn’t rude or off-hand: there was always some enquiry after Mr Elliot’s opinion of the weather, or about a new product that had caught his eye. Polite. But he had never once even so much as asked after the shopkeeper’s heath, nor given any indication as to his own. A man that liked to keep himself to himself; Mr Elliot could respect that.

Andy was in the Household aisle now, comparing two brands of toothpaste. Of course, in the end he would choose the Signal, like he always did, but he studied the boxes closely, as if for the first time. He was an odd young man, that was for sure. Harmless, most probably. That’s what the owner of the village’s previous shop had said. He had told Mr Elliot about Andy as part of his grand tour of the village characters. He had explained that there was tragedy there, family business, that the lad had had a hard time. He could be odd, but he was harmless. It had been a good family, before the accident left Andy on his own. He’d have been about eighteen then. There’d been a brother, a twin, but no-one was sure had happened between them; the brother had just upped and left a few months after the funeral. You’d think that twins would be closer, but never underestimate what grief can do to a man. Thinking about it, it was no surprise that Andy kept himself to himself. In a situation like that, privacy was the least you deserved.

Bee-boo.

Gary swung into the shop, shouting his greeting before he’d made it more than a few feet inside the door. Too much swagger, too loud. Mr Elliot smiled despite himself and answered with a cheery “Morning, Gary. What’ll it be?” He was leaning on the counter now, and Mr Elliot could see the black-blue tendrils of a tattoo snaking out from under the sleeve of his T-shirt.

“Twenty Benson. And…” Gary rifled through the chocolate bars stacked neatly in front of the counter. “…one of them.” He tossed a Mars Bar onto the counter. Mr Elliot smiled again and turned to the cabinet behind him to find a packet of Benson and Hedges cigarettes.

“I see the weirdo’s in.” Mr Elliot didn’t need to turn to know that Gary was nodding in the direction of where Andy was checking the dates on the milk. “I don’t know how you cope, I really don’t. Patience of a saint, Mr Elliot, that’s you.”

“Indeed.” Mr Elliot smiled at his cloaked rebuke. “That’ll be thirteen fifty seven.” While Gary fumbled through his wallet, Mr Elliot held out the card reader beatifically; when it came, the reassuring beep settled him somewhat. A village shop was a precarious business, and you couldn’t afford to turn your nose up at trade, even if you didn’t like who brought it.

Gary pushed the chocolate bar into the back pocket of his jeans and started to pick at the cellophane seal as he walked towards the exit. His fingers trembled with anticipation. Anticipation or addiction, Mr Elliot thought to himself derisively as he watched his first customer of the morning sweep though the automatic doors.

Bee-boo.

As if by magic, Mr Elliot’s second customer of the day presented himself at the counter, waiting patiently until the shopkeeper’s attention had returned. He stared at the hand gripping the handles of the over-full basket as if it belonged to someone else.

“Morning, Andy. It’s not the brightest, is it? D’you think the wind will shift it later?”

Mr Elliot reached out a hand to take the basket onto the counter.

“Not much wind. Think it’s set for the day. Might yet be some rain. Smells like it.”

Mr Elliot started to decant the contents of Andy’s basket, swiping each across the barcode reader until the beep told him to move on to the next item. Two cartons of milk, semi-skimmed; two thick cut white loaves; a bag of carrots, then another; two cans of chunky vegetable soup; two of luncheon meat; two pairs of rubber gloves; two packets of cheese slices; two apples; and two tubes of toothpaste.

“These are cheaper if you buy a third. Three for the price of two.” Mr Elliot said this knowing that the offer would be declined. It was simply a shopkeeper’s duty to alert customers to the best value, and he carried on without pause.

Two cans of Coca Cola, full fat, and two pats of salted butter from New Zealand completed the list. Only once every item had been scanned did Andy begin the task of loading his cargo, two by two, into his shopping bag. He took care to ensure that the heavier things went in first, and finished the job by neatly arranging the two loaves across the top. He hefted the bag from hand to hand, assessing the weight balance, and then placed it on the floor beside his feet while he rummaged in in his pocket for his wallet.

“Paper, Andy? You take the Mirror, don’t you?” Mr Elliot reached over to the stacks of newspapers that had yet to be arranged on the rack. He paused. “Two?” Andy nodded and Mr Elliot took the top two copies from the pile of Mirrors and scanned the first one twice. Beep. Beep. He folded them, separately, and handed them to Andy to place in his shopping bag.

“Right, so that’s twenty nine fifty eight, I’m afraid.” Mr Elliot reached for the card reader out of habit, but stopped himself in time. Andy held out £30 in two notes. “That’s fine, Mr Elliot. Just put the odds and sods in the charity box.” Andy picked up his shopping bag. “Thanks. I’ll see you soon. Make sure you’ve got a brolly for later – trust me, it’s going to pour down.”

Mr Elliot watched as Andy trudged out. Bee boo. Once the doors had hushed shut behind him, he looked at his watch and, with a sigh, made a start on setting out the papers. Mr Arnold would be in for his Daily Mail soon.

The bag’s handles dragged down through Andy’s knuckles and he wished the police would get bored and leave him in peace. The last time they’d come was the night his parents hadn’t come home, had left the car and themselves smeared across the old railway cutting. They had come to help, they’d said, to make sure the boys knew, to make sure they were alright. As if they could be, in the circumstances. He’d not wanted them here then, and he didn’t want them here now. He thought about his brother and he stiffened. He’d already lost his parents. He couldn’t lose Jake too. Not after all these years.

The milk would curdle soon. Andy looked into the bag. The softness of the bread, squeezed against the plastic of the wrapping, looked like it might burst; time ticked by on his wrist and his mind raced in calculation. There was no way of knowing how long they would wait for him, no way to judge whether it was worth laying low, yet he still raced between the variables, weighing his options. Five minutes, he thought. He’d give it five minutes and if there was no sign that they were starting to lose interest, then he would grit his teeth and confront them.

Almost as soon as he had made his decision, one of them, one of the ones near his door, turned towards the one in the peaked cap and shook his head. He started to walk back into the yard, but the one in the peaked cap shooed him back, his hand tumbling in frustrated encouragement.

“Shall I force this?” The one next to the barn held the padlock in his left hand as he waited excitedly for permission from the one in the peaked cap.

“Do we have a warrant? No, we do not. So don’t be a stupid bugger. Keep looking around.”

The one in the peaked cap wafted the back of his hand in the direction of the barn, exasperated. The other slunk off dejectedly, his shoulders closing around his chest. Andy watched him disappear behind the corner of the barn, where he kept a stack of fluorescent lighting tubes. He no longer remembered why he had them, nor why he thought they might be useful one day, but he had the space and nowhere else to put them, so.

A smile crept up on him and the thought bubbled up, releasing his apprehension. They didn’t have a warrant. Andy had watched enough television for this small, hard fact to embolden him. He gripped the shopping bag and walked into the yard.

“Morning. What can I do for you, then?” Andy did not stop as he passed the one in the peaked cap, didn’t even turn to accept the reply, and he headed towards the house, as if unconcerned.

“Mr Sturrock? I…” Andy could hear the one in the peaked cap trotting up behind him as he fished about in his pocket for the house key. The two that had been by the house had parted as he’d approached and stood watching, bemused. “Mr Sturrock, please. I just need a word.” He was almost panting. Too much time behind a desk, not enough chasing villains, Andy thought. “We’re following up on some enquiries and I hoped you would let us take a look around.”

The key slipped into the lock and the latch clicked with welcome familiarity. One foot inside the door, Andy turned to face the one with the peaked cap. “Do you have a warrant then?” He watched the face fall, then tighten. He couldn’t see them, but felt the other two by the house shift uncomfortably.

“Am I to understand, Mr Sturrock, that you do not intend to allow us to search the property?” He had thin, watery eyes, grey and weary. He was getting on. Almost time for retirement, Andy thought. Not much spark there, no hunger. Andy felt his confidence grow and he smiled as he confirmed that, no, he would not allow them to search his property, that if they really felt the need then they should go get themselves that warrant. He pushed the door behind him and left them outside. He pictured them standing there, gobsmacked, not sure what to do next. The rising impotent anger of the one in the peaked cap was palpable. Andy could smell it. The kind of powerlessness that tasted bitter when it was his own, but smelled sweetly to him now it was on someone else. He allowed himself a moment or two to enjoy the strange sensation. If the milk were not turning, he would most probably have stood there until long after they had tumbled into their cars and driven off defeated.

They were not defeated, of course. As Andy stowed one of each item from his now empty shopping bag in its rightful place, the certainty of their return filled the room. They would come with that warrant and there would be nothing he could do about it. He looked at the items remaining on the counter, the other half of his shopping. Exactly half. He held the apple, studied its glossy skin minutely, absorbing every freckle, and the blurred borders between red and green. Time would take it all, eventually. Time would take everything.

The rain had started, as he had predicted, and he crossed the yard stooped and flinching against every heavy drop. Above him the sky glowered, mottled with pigeon colours, and the wind sheered down and chased itself about the buildings. With his free hand, Andy fumbled the key into the lock and the barn door creaked open.

Inside, he shook himself and the shopping bag and a spray of droplets arced into the half-light. The barn smelled stale, with a tang of decay. Ahead of him, a corridor between two runs of shelving disappeared into the darkness; the point where it turned square to the right was just beyond sight, but Andy knew it was there. He had no need for electric light to navigate his labyrinth, laid out over the last ten years, but he clanked the switch anyway and fluorescence bleached the space. This could be last time he saw it, after all.

Just before the first corner, Andy paused and rummaged in his shopping bag. He took the can of Coke and placed it on the shelf that housed the soft drinks; a few feet further, he did the same with the rubber gloves, squeezing the packet into the last remaining space. On he went deeper into the maze, stopping at a stack of shelves, a crate of rotting vegetable matter, or an unruly stack of tins teetering on an old palette. Ten year’s accumulation of his shopping: every duplicate stored here. Stored for Jake. For his twin.

It had begun shortly after their parents had left them. Something about the precariousness of life had provoked in him the need to ensure that every last thing had a replacement ready and waiting. The compulsion to duplicate every purchase had initially been limited only to consumer durables, to clothes and gadgets, to necessities for the farm. Just in case the original broke, or was lost. Jake had laughed, then had become concerned, then scornful. He started to talk about leaving at this point, and Andy’s need changed. Everything he bought, he bought as a pair. One for him, one for Jake. That was when Andy sold the pasture and adapted the barn. The labyrinth grew from there.

Andy was getting nearer to the centre now. The path wove its way aimlessly, inscrutably. Even with their warrant, it would take the police an eternity to pick their way through it. Likely they would find nothing untoward. He knew that his store was a little eccentric; that the people in the village saw him as odd. Even Mr Elliot, although he at least had the courtesy to keep his thoughts to himself. But no matter how odd others thought him, oddness was not a crime. Andy dropped the loaf of bread into the crate. A cloud of blue-grey dust billowed upwards.

He was at the centre now and all that remained in his shopping bag was the paper. He had no idea if Jake like the Mirror. He hoped so; hoped his brother had matured in the same way that he had. As teenagers they’d never really bothered with that kind of thing. More interested in girls and cider. Then the accident had happened, and the troubles of the world became utterly irrelevant. It was only later that Andy had started to take a paper, and the Mirror had been his dad’s choice, made for him in the womb.

Andy unfolded the paper and scanned the headlines. Something about the NHS and politics. He flipped it over to look at the sport, but he had no interest in that either, so he tossed it onto the huge stack that would surely soon give way. But not today. The stack was strong enough to last today.

Andy looked at the patch of ground in front of him. It was the dead centre of the barn and the only space in it that was big enough to swing a cat. When you stood here, he thought, it’s kind of obvious. If the police found their way through the maze, then it would be obvious to them too. They’d be curious at the very least. Andy shook his head and tried to think.

He shouldn’t have said he was going to leave him, not him as well. He’d said that he couldn’t stand it anymore, that he was fed up of babysitting his mad brother, that he’d be better off somewhere else. It wasn’t fair. Andy was only just managing to cope with their parents leaving, and he wasn’t going to let that happened with Jake too. And so he had stopped him. He wouldn’t leave the farm, leave Andy, not ever.

Andy looked around. Perhaps he could shift one of the stacks onto the empty space, cover it up, make it look like the rest of the barn. He looked at the pile of newspapers, calculated how long it would take. Too long. And they’d be able to tell, anyway. They could tell things like that. They had training. Even if he shorted the lighting circuit so that it was dark, they’d know. Whatever he did, they’d know.

He trudged back through the labyrinth. He paused at the shelf with the cans of fizzy pop and picked up a Fanta, tugged at the ring pull. The bubbles fizzled on his tongue and he felt like a child again, if only for a moment. Then he was by the door, where he kept the turpentine. He put the Fanta on the floor carefully and picked up a gallon jug.

Back at the centre of the barn, he emptied what little was left in the jug onto the newspapers. He thought about finding something nice to eat, one last treat, but decided there wasn’t any point. Instead he stared at the patch of ground and felt the tears form in his eyes. He fumbled with the lighter he had taken from the pile of lighters on the shelf near the batteries, and his shoulders convulsed with his sobbing. Ten years too late, he let out the grief, let it pour over the world like turpentine. He could barely spark the lighter into life, he was shaking so much. There was a low animal wail in the air, and Andy tried hard to trace it, never knowing that it came from his own mouth.

- Disconnected

It was a rather ordinary street, yet even for this part of north London it appeared exceedingly polite. Two neat terraces of Edwardian houses, complete with bay windows and brick-arched doorways, faced each other across the too-straight road. The brickwork and pointing was clean and sharp, the sills and window frames painted to a pristine white. The small front gardens were always tidy, in an understated way. The tastes of their owners were expressed only in muted tones. Along the street itself, the pavement was punctuated in an orderly fashion by mature plane trees, their pale bark flaking – but only in so far as was consistent with the accepted behaviour of the species. Even the ruptured flagstones, forced up over long years by the flexing of roots, was seemly. Elsinore Road was much like every other street in this comfortable enclave. But this morning, from the corner with Cawdor Street, it was disturbingly unfamiliar.

He passed this junction every morning at about this time. Early enough that his ritual did not needlessly delay his departure for the office, but not so early that he had to make the walk in darkness, even in the depths of winter. That day, like every other day, he had drained the last of his tea from his Arsenal mug, pulled on his sweater, and tightened his laces before setting off with Moses.

It had been Moses, pulling at the lead, that had made him turn to look along Elsinore Road. Squirrels, he had assumed. But instead of the expected flash of bushy greyness, he was met by a sight that brought him up short. Instinctively, he wrapped another turn of the lead around his hand, ready to restrain Moses. This was not something he should be rushing into. There was no tug however, and he felt a pride at his dog’s good sense. There, in the middle of Elsinore Road, squeezed between the two rows of cars parked along its flanks, was an abandoned double decker bus. It was on fire.

Even after several moments of reflection, it was unclear to him how the bus might have come to be there. Certainly, there had never been a bus there before. Elsinore Road was, put simply, not on any recognised bus route. It was therefore unlikely that there had been some kind of straightforward accident, necessitating a sudden evacuation. The fire, while possibly supporting the accident thesis, would seem to rule out the idea that one of the residents had hired the bus for some event – a wedding maybe – and had simply left it there pending the appropriate departure time. Regardless of the other circumstances, it would have been highly inconsiderate to block the entire street in this way. He had seen some things in his time, acts of colossal thoughtlessness, verging on abject selfishness, but even in this day and age it seemed unlikely that one of the residents of this street would have behaved with so little regard for his neighbours.

And then there was the burning, of course. That would seem to argue against the deliberate parking of the bus, even allowing for some monumental carelessness for the convenience of others. He checked briefly for some sign of a film crew, just in case – such things happened in London – but that theory too evaporated before it had fully formed.

Foul play then. No other explanation presented itself. He knew of course that occasionally cars were abandoned in the area, left by joyriders fleeing the consequences of their thrills. Two years back, a still-smouldering Vauxhall Astra had been found parked on the grass by the flats at the top of his street. By the time he had heard about it and made his way there to take a look, the metal was deathly cold, but he had been struck by the waywardness of the parking and the damage done to the turf. Both reeked of wantonness, even without the arson.

Joyriders. He found himself saying the word out loud, rolling its absurdity around his mouth. Moses looked up at him, perplexed, head cocked, and he felt embarrassed. And yet there was no-one around to hear him, aside from Moses, and Moses was not at all judgemental. The emptiness of the street suddenly surprised him. Such phenomena always attracted curious onlookers. Quite a crowd had gathered to look at the Astra, even if everyone had pretended that they had simply been passing, going slowly about their business, heading to the shops or wherever, and had been only momentarily distracted by the blackened husk of the car. But here there was no-one. Elsinore Road was empty, aside from the silent cars and steadily flaking trees. And the bus of course. He craned his neck to peer past it, to the far corner, but no-one stood at the junction with Belmont Road either.

What’s more, there was no police tape, no fire engine. No sirens. Surely a burning bus should attract more attention. Surely it demanded a response from the emergency services, notwithstanding the undoubted budget cuts that such services had endured in recent years. Surely they would have turned out for something like this when asked.

A thought occurred to him and he looked along the street, his eyes coming to rest at the window of each house. Each was a blank pane, reflecting the street back onto itself. Occasionally, he thought he caught a glimpse of movement, a flash of life, before the glass settled back into liquid stillness. The street’s residents, he decided, were aware, were looking on, but were doing so in fear, or maybe simple indifference.

This last thought chilled him, before sparking an anger within his chest. He felt his pockets, patting each in turn with careful palms, but found nothing. He knew this would be the case. This was one of his pledges to self-improvement that he actually observed. His mobile phone was on the kitchen counter, left there so that his walk with Moses could happen without the intrusion of the infernal thing. Weeks ago he had made the decision, seemingly unable to resist the ping and buzz of any of the email accounts or the social media channels to which he was inexplicably connected. He was not old, dislocated, nor technophobic. Later, at the office, he would log in to the same systems as those twenty years his junior. And yet he failed to see the point of Whatsapp. It was simply a constant nagging of ephemera, insistent and urgent, yet utterly unimportant. Whatever those pings demanded could wait, at least for half an hour. They were like a tugging at one’s sleeve while one read, or talked with a friend. A real friend, one who had taken the trouble to occupy the same space in the world. A friend like Moses.

So he had decided that each morning he would leave his phone on the kitchen counter, and he had been true to his word. The chaos of the world had been left behind for thirty minutes as he took his circuit around the neighbourhood and it had been blissful. His easiest resolution, and one about which he had had no regrets. Until that morning, when the chaos of the world had found him on the corner of Elsinore Road and Cawdor Street.

He looked along the blank windows once more. Surely one of their hidden occupants must have called for the emergency services? Surely. He strained to listen again for sirens, but nothing spiralled above the dull hum of the morning air. Even the birds: often the chirrup and cheep of unseen birdsong fell from the trees like crumbs, but today there was nothing. Just the hum of distant traffic and the closer crackle and whoosh of the flames.

The flames. Against his better judgement, he moved forward. There was nothing for it but to investigate himself. With the lead turned tightly about his hand, he approached the bus, conscious of the tank of diesel somewhere in the guts of the burning hulk. He could feel Moses’ glances up at him, anxious, as together they advanced.

He stopped a few yards short of the bus. Through the smeared, sooty windows, he could see insouciant flames swaying over moquette upholstery, in a languid, drunken dance. Everything else was lifeless, paused. The doors were ajar, caught between open and closed, frozen in their transit. But there was no driver behind the wheel operating them. He looked into the bus once more. No-one appeared to be inside, alive or dead, and he felt a little gasp of relief slip from between the clenching of his chest. He gave up any notion that this might have been some kind of accident, and was further grateful that today would not reveal his first corpse. Not yet anyway.

Behind the bus, he heard the sound of a front door closing on the far side of the street. He was filled with unexpected joy to no longer be alone with the bus. Another had come to join him in confronting the unprecedented conundrum. He tried to catch a glimpse of whoever it was through the bus’s windows but to no avail. He hesitated for some moments, unsure whether to move to the left or to the right, and before he had reached any definitive conclusion he saw a young woman. She was dressed for an office rather than for action, and was walking away along the pavement, heading in the direction of the tube station. He watched her for an eternity but not once did she glance over her shoulder to where the smouldering bus filled her street. It was as if such things always loomed outside her front door, that burning buses were a frequent occurrence on Elsinore Road. Forlornly, Moses barked after the woman as she turned the last corner. The bus crackled on.

A swelling of irritation flushed through him. These people seemed unconcerned by the threat sitting on their doorstep. The concern had been left to him. It wasn’t even his street. He looked along the line of cars that fringed the pavements. Smart, expensive cars parked adjacent to a huge petrol bomb. He thought about the blank windows of the houses, about the impact of the inevitable blast upon them. In the circumstances, the apparent lack of concern on the part of the residents was baffling and frustrating in equal measure. If such a thing had occurred on his street, he was convinced that his neighbours would have taken action. He looked again at the dismissiveness of the houses and wondered if in fact his neighbours would be any different. Perhaps, in the face of such a thing, the most natural response of all was to carry on as if it wasn’t there. Perhaps he was at odds with the world, rather than the other way around. He looked down at Moses.

“I am I going mad, boy? What do you think? Should we take charge?”

It was always going to be this way. Were he honest with himself, he would acknowledge the slight thrill he felt at the responsibility falling onto his shoulders. It was left to Moses, his doleful eyes turned up towards his master, to remind him that he would have felt frustration rather than relief, had the police already been there. Even the presence of the inhabitants of the tidy houses themselves would have inhibited his sense of usefulness. Usefulness. It seemed too small a word.

But there were no police, no fire crew; no concerned people of any kind. He was indeed useful. With a too-loud sigh that prompted a sceptical whine from Moses, he turned towards the other end of the street, to Belmont Road, walking with purpose and resolution. If he remembered rightly, there was a phone box on Belmont Road, just a little way beyond the corner. From there he would call the emergency services, even though his car, his windows, were not in jeopardy. He allowed himself a little frustration at the inaction and elusiveness of the residents, and its swelling filled his chest.

Moses relaxed once the bus was hidden behind the corner of the street. He trotted contently at his master’s side, his legs a blur beside the man’s long and even gait. In a moment they had reached the phone box and the two of them squeezed inside. Only then did the fetid smell and filthy interior present themselves, causing the man to gag slightly, his stomach clamping shut like an oyster. It took a moment for him to summon the wherewithal to touch anything. It had been a while. The mobile phone had effectively ended his relationship with the phone box, but without fanfare. He had simply stopped noticing them one day, consciously at least: this one had, after all, found a way into his memory. In his earlier years, the location of the familiar red cabins had been an important piece of knowledge, an essential part of living in town, yet now they were ghosts, things for the tourists, not for real people. Most of these heavy iron boxes had been removed years ago, but this one had survived, somehow. Albeit it in a terrible state of disrepair.

Cautiously, he lifted the receiver and tamped down on the hook, hoping against the odds that the line might spring into life. Memories of testing the line as a student, so that he might make his weekly call home, came back to him; calling friends to let them know his train had been delayed. Memories stretching all the way back to when his relationship with the phone box had begun as a boy. When, as a cub scout, he had learned to drop the two pence piece into the slot once the pips started, so that he could report any emergency. There was no slot for a two pence piece any more, but that early training would now pay off.

The stickiness of the receiver in his hand evoked so many unwanted thoughts that he was grateful for the certainty of his task. Still, he held the earpiece an inch from his head, such that he could not be certain if the dull drone was the purr of a dialling tone or the shriller whine of the line’s unavailability. Feeling optimistic, he began to dial, pressing the nine key three times. It too was sticky to his touch and he began to wonder if this was simply his own perspiration. He waited, while the drone at his ear droned on.

There was a loud thud, some vibration, the sound of breaking glass, of car alarms. Moses whimpered and quivered, his eyes pointing down at the floor rather than to the source of the disturbance. The man, too, did not turn towards the blast, knowing that everything would be hidden by the corner that turned into Elsinore Road. Too late. He tamped angrily on the hook, trying to spark some life into the phone, but the dull drone simply droned on. No one would come, at least not at his behest. Maybe someone else, someone on Elsinore Road, had by now called 999. It didn’t matter. The drone in his ear smothered the shrillness of the car alarms, filled him until it was all there was.

- Fuse

He is there again. Alone, as usual, lost somewhere, past the tables and the teacups, the shops and the neon. His tea must be cold by now. It is practically untouched, although the ashtray is filling steadily. He rolls the thinnest cigarettes in the world. His whole face puckers to suck in the smoke, the thin crumple of paper pinched between the thumb and forefinger of his left hand. The nails are bitten back; the skin on his finger ends too. His cuticles are rags. His herringbone coat, shrugged from his shoulders, hangs from the back of his chair. Its torn lining spills its guts in voluptuous coils; he looks as if he is sitting in the remains of some disembowelled beast. Alone, as usual. His aloneness is captivating.

She snatches what glances she can across the cafeteria’s muddled congestion. Around her, there are explosions of laughter, of sarcasm and innuendo. Jinksy, raven hair streaming down over his heavy black coat, is on form today. The girls are swooning over their tea and flapjacks; the boys are sullen, cowed. Sometimes one will try to capture the conversation, to impose himself on the table, to say something funnier, ruder, cleverer. But Jinksy, Jinksy is having none of it.

It’s like this every Saturday. Whatever else happens in the week, by 3 o’clock on Saturday afternoon everyone in town, everyone interesting, has gathered in the Friary to boast and brag, to be seen, to watch. She fell in with them earlier in the autumn, and they are her family now, whenever she is in town. Which is every Saturday. What else would she do?

She met Jinksy through Leonie, the friend she made on her first day of college. Leonie knows Steve, went to school with him, and Steve knows Jinksy. Worships Jinksy would be more like it. No longer at college, Jinksy is unemployed and spends his days writing desolate poems in his bedsit up by the Garibaldi. Someone said that he sleeps in a coffin. A real, actual coffin. Part of her can believe it, but when she pictures the scene she wonders if he has a duvet, a pillow, if it is a new coffin, or a second hand one. A used coffin. She stops herself then, not wanting that thought to linger. She is disturbed by her easy slip from the banal to the macabre.

So Alice sits with Jinksy and Steve and Leonie and the others, and tries to pretend that this corner of a provincial shopping centre is the coolest place on earth. Certainly the coolest place in her rubbish, tawdry town. At least here with her friends the only currency that counts is a knowledge of music and movies and books. Alice brings books and Leonie, music; they nod ponderously at the mention of films they haven’t seen, directors they’ve only read about in the NME.

Leonie tilts her empty teacup towards her and peers down to confirm its emptiness. Unthinking, she reaches over and takes the little metal teapot sitting in front of Alice and pours the last of its contents into her own cup. Only then does she think of her friend and, coyly, offers a piece of her flapjack. Alice declines. Instead she looks at Leonie, at the pale face behind heavy black eyeliner, at the piece of purple lace tied into her henna-red hair.

She wonders if she only made friends with Leonie because of her clothes. When they met, in the queue to sign up for English Lit, she looked like the kind of person with whom Alice had decided to surround herself in her new incarnation at college. She was alone; no one from her school had gone to college. They had either left to find jobs or stayed on in the sixth form. She had despised the lack of imagination of the workers and the timidity of the rest. She couldn’t understand why anyone with the chance would not choose to rewrite themselves. Only now was she beginning to understand that the potential for reinvention is finite. The self you show to others sort of sticks to you. Unless you get it just right, first time, it will grow to bind you, to ensnare you, just as much as the things you are trying to leave behind.

Leonie now seems like more of a constraint that anything else, but how had Alice been supposed to know that? Leonie had been so much cooler than anyone she’d met before, certainly more so than anyone at her suburban comprehensive, where the girls liked Duran Duran and the boys pretended not to. In the queue, Leonie had been so exciting, so open to everything. Within minutes, she had told Alice that her brother had been at school with the bassist from Bauhaus, and this slightest of coincidences had seemed like proof of Leonie’s specialness. Alice had marvelled at the confidence, the self-assurance, and the glamour of this girl in black and purple, who stared at the world with an insatiable hunger.

Now, two months into the first term, Alice is bored of her friend’s vacuous insincerity. She still has the clothes, and her knowledge of gothic punk is encyclopaedic. But there is nothing there, just surface, shallow and plastic. She is a perfect facsimile of cool, which is by definition not cool. And now they are tied together: until she can escape to university, Alice is simply one half of Alice and Leonie.

She looks from her friend to her teacup, to the little empty teapot, and back to Leonie.

“I’m going to go get some more tea. Anyone want anything?”

She already knows what she is doing, that she will not go back to the table, at least not yet. She orders two teas and a millionaire’s shortbread. The woman in the brown checked tabard smiles as she takes the carefully counted stack of change that Alice slides across to her. The crockery rattles wearily onto the tiled counter.

She can feel the eyes falling on her back as she passes the table and continues through the emptying café to where he is still sitting with his cold tea and his red carnation. Her red carnation. She had given the flower to him, earlier in the day. Leonie and she had been circuiting the centre, as usual. He had been wandering in and out of Revolver and W H Smith. She had recognised him from previous weeks. As usual, he was wrapped in his oversized coat; an unruly mass of snags and knots emerged from beneath the peak of a cotton cap.

His haunted eyes had searched the dark marble walls and shop windows, but never rested anywhere long, never gave you to believe he was seeing what you were seeing. She knew Leonie wouldn’t approve. Maybe that was part of the attraction. She had wanted to say something to him for weeks, but had never had the courage.

Until today. Today she had decided.

She had bought a single, blood-red carnation. Leonie had gone with her despite her misgivings and had even been polite when they caught up with him outside C&A. Alice had told him that she and her friend had been judging a Best-Looking Man competition and that he had won, that the flower was his prize. She had held it out to him, stretched across her two upturned palms. He was probably eighteen, maybe older, but for a moment he looked younger, unnerved and embarrassed. He had asked if it was a joke, had expected the girls to burst into laughter. But Alice had assured him that the judges’ decision was final. He had bowed slightly, Alice thought, when he had taken the flower.

“Remember me?”

Of course he remembers. How could he not? Her gesture had been well-judged, both knowing and innocent. A flower. Not a weighty rose, but something light enough to brush aside if need be, yet meaningful enough to capture attention, to convey intent. She pushes one of the cups towards him across the Formica and takes a seat opposite without waiting for an invitation. Her sudden capability intoxicates her.

He looks at the tea, at the fingers of his left hand, then up at Alice through the cracked ends of his unkempt fringe. He has brown eyes. Soft, like a cow’s. He says thanks, indicating both the tea and the carnation, before pushing the plastic wrap of Old Holborn towards her. Alice shakes her head in a tight, rapid vibration, her lips pursed. Instead, she cuts the shortbread in half, and then into half again, then she cuts each of the four new squares on the diagonal, so that the plate is littered with triangles and crumbs. Alice drops one of the triangles into her mouth before pushing the plate towards him.

“I’m Alice. Pleased to meet you. Properly, I mean.”

He looks at her primly extended hand, smiles, and simply dips his head in acknowledgement. There is no handshake; Alice wrestles with her awkwardness.

He is called Hal, but not like Henry IV; like the computer in that film. Alice rides over her disappointment and is off, telling him about herself, about college, about the music she likes, the books, a sudden flurry of facts and positions. Hal watches, waits. While he asks no questions about her, neither does he fill the space with his own voice, his own opinions. Alice is aware that this unnerves her. It is unexpected and unusual. His quiet command of this table, his table, is so much more complete than that exercised noisily by Jinksy across the way. She can hear the blood thumping behind her ears.“What about you?”

He looks puzzled, but still says nothing, only watches.

“I mean, are you at college? What music do you listen to? That kind of thing. I mean, I feel like I’ve been boring you rigid with my life story, and yet I don’t know anything about you.”

“Why would you want to?”

Alice is about to answer honestly but catches herself. She would be giving away far too much far too early. So she says simply that that is how conversations are meant to go; it is the normal way of things. Hal’s nostrils flare slightly, but he answers her questions nonetheless. Eighteen years old, he works in a record shop, saving some money to go abroad for a few months before university next autumn; for now he lives at his parents’ house. He listens to The Smiths and the Jesus and Mary Chain rather than the Cult and Fields of the Nephilim; he watches Lynch and Cronenberg, reads Kundera and Camus.

“Alice? I’m going, mate. Jinksy and them have already headed off. Do you want to get the bus with me, or what? They’re shutting the place up.”

Leonie is standing behind her. Alice knows, if only from Hal’s face, that while Leonie is talking to her, she is staring at him with something like disgust.

“No, I’m going stay for a bit.”

Alice turns in her chair to offer a smile to her friend, adding: “You remember Hal from earlier, yeah?” Leonie manages a dismissive nod in Hal’s direction. Then she is gone and there is only Alice and Hal. In the conspiracy of solitude, both the posturing of Jinksy and the limits of Leonie become brittle and plastic. Hungrily, Alice soaks in the depth of Hal.

“I fucking hate this town. I mean, why would anything sentient want to live here, right? It’s like they put something in the fucking water. Like the air is dosed up with something.”

His anger is sudden and shocking. He draws furiously on the cigarette that has been resting extinguished in his left hand for ten minutes. In the end he gives up on the idea that he can re-ignite it with his own incandescence, and leaves the cigarette between his lips and reaches for his lighter. Sparks splutter before a shallow dome of orange flame settles into being. It is at this point that Alice notices that his right hand is planted firmly in his coat pocket.

Metal shutters clatter down behind her, signalling that the counter is now closed. It is five o’clock, and she has been sitting with Hal for almost an hour. She realises that during this time he has been doing everything – smoking, drinking tea – one-handed. She frowns, squinting at where his right hand disappears.

“You left-handed?”

He shakes his head. Something flickers behind his eyes, and he leans in slightly across the table. His voice lowers.

“Shouldn’t really tell you; might freak you out. Let’s just say I’ve got something in my pocket that I’m… I’m keen to hang onto.”

The woman in the brown tabard ignores them as she shuffles past, towards the bus station. Over the chocolate acrylic of her workaday uniform, she is wearing a blue quilted coat trimmed in scarlet, but she is unconcerned by the inappropriateness of her choices. Watching her leave, Alice does not need to turn around to know that there is no-one left in the courtyard of the cafeteria, that the little shops that surround it are either shut, or shutting, or empty. Her vulnerability nags at her shoulder.

“Alright, look. Do you promise not to go mental if I show you?”

He too is aware that they are alone, that there are no witnesses to whatever secret he is about to share. Alice knows that this is a moment to test her presumed audacity; that to hold back now is something that Leonie would do. The person she has willed into existence would embrace this. She knows that the world will hold bigger shocks and terrors than anything that Hal could carry in his coat pocket. She studies his face, his eyes, looking for any trace that he might be some sort of pervert.

“Yeah, go on then.”

Needlessly, he looks over both shoulders. His eyebrows twitch upwards, maybe as a warning, or perhaps as a drum roll. His right shoulder drops as his arm snakes out from under the folds of gabardine; Alice looks only at his eyes, does not want to uncover the mystery earlier than is necessary.

He has stopped squirming in his seat, is still, expectant, yet her gaze remains fixed on his face. Impatient now, he nods slightly, eyes widening, to where his hand must surely be beneath the Formica. She leans around, hesitant, boldly, to see. Under the table, he clutches a hand grenade.

“Fucking hell! I did not see that coming! I thought it was going to be something sleazy…”

Alice laughs a nervous laugh, a flash of mischievous delight on her face. She knows that to Hal this is serious, but she cannot contain her relief, the joy of finding something so outrageous in this humdrum shopping centre, in this pointless town. Before she can ask where he got it from, whether it worked or not, Hal is talking again, his voice level and confident, but maybe a little too cold, a little too rapid. There is anger still, but no bile, no blood and heat, just iron detachment as he explains that he had taken the grenade from his father’s collection.

“Another time, another place, he’d be a fucking Nazi or something. He’s got knives; I mean big knives, by the bucket load; rifles and that, too, most of them replicas. But not all. That’s how he keeps himself anaesthetised: pretending to live in some made-up Second World War adventure. He comes home from work and numbs the boredom with all this… It’s real, you know, I’m not messing about.”

“What do you mean? Not messing about?”

Before she reaches the ‘b’, she sees that Hal’s hand is clamped hard on the lever, that there is no pin in the mechanism.

“Where’s the pin, mate?”

“Don’t know.”

She doesn’t have time to ask what he means by this.

“I took it out this morning, threw it in a bin on the market square. I’ve been carrying it round, primed, all day. Locked in. In case I start to wuss out.”

Alice remembers that he had taken the carnation with his left hand earlier on. Even then.

She is angry now. There is living on the edge and there is being bloody stupid – she can hear her father’s voice in her head, and strives to shake it out. Looking at the floor, she struggles with the ‘w’ of why or what, or any number of questions that are jostling inside her mouth.

“Wuss out? Wuss out of what? This is messed up, man.”

For some reason, as if it made anything better, Hal slides the grenade back into his coat pocket.

“Look, I was never going hurt anyone. Just, you know, make a mark. I was going to wait in the centre until it had all shut up, then throw this at the shop that’d pissed me off the most today. C&A most likely. Maybe Chelsea Girl. Hadn’t decided. Probably C&A.”

He laughs then. The conviction is gone, and he is left only with uncertainty and a live grenade. Alice reaches out to touch his free hand and his eyes soften again. She asks what he plans to do now, knowing he has no plans. His not knowing is reassuring.

Abruptly, Alice pulls a scrunchy out of her hair, then a second, and hands them to Hal. She explains, in her impatient adult voice, that he should secure the lever of the grenade with them, that he should still hold on, just in case, but less fiercely than before; she has an idea, a way out of this, an alternative to the demolition of C&A.

She is all bustle and motion, collecting her things and leading him out of the deserted cafeteria and past the bored and vacant stores, which are killing time until they are allowed to close at last. He offers no resistance as they plunge out of the yellow brightness of the arcade and onto the already dark street. Despite herself, Alice is thrilled by their secret cargo, the potential it carries, and the ignorance of the stubborn shoppers and eager drinkers that coalesce on Abingdon Street.

She leads him down Fish Street, then out along Derngate, as far as Becket’s Park, its darkness ringed by the insidious sodium glow. They push on into the blackness, darker yet under the trees, and towards the looming bulk of the perfume factory across the river. They are laughing now, giddy in their freedom, in their adventure. Alice squeals, exuberant, as they trip over their heels, tumbling down the slope towards the light band of water, luminescent orange, distinct among the shapes made up of shades of black. At the bottom, by the swings, they stop, sucking air into their lungs, shaking out their remaining laughter.

There is low lamp light here, and they sit on the wooden boards of the little roundabout. He struggles to roll a cigarette with his free hand, and Alice asks if she can hold the grenade, to make it easier; they exchange a look, and he hands the weapon to her, his pupils dilating so wide that she sees all the world reflected back in them.

“It’s not my real name. Hal, I mean. I lied. I’m sorry”

But Alice does not mind and her eyebrows rise in encouragement. He stares at the glowing tip of his cigarette, searching for the words or the courage or another, better lie. Eventually, he tells her how he hates Phillip, hates his parents for imposing it upon him, how the decision to name himself anew had arrived late one night in front of the television. She feels the warmth crackle between them and pulls him to his feet once more.

Across the first bridge, then the second, past the factory and its empty car parks. The tarmac melts to gravel, and they are on rough paths. The intermittent street lights disappear, and only the orange sky illuminates their careful navigation of open ground. Alice still holds the grenade, will not give it back, refuses to surrender either the responsibility or the thrill. She weighs the potency in her palm, needlessly clasps the lever’s spring in her trembling fingers, tastes the sweetness of latent destruction, its power.

And then it is there: the rippled slab of water, phosphorescent. Pocked with dark clumps that she knows to be islands. Above them, a stream of light slides off the edge of the dual carriageway, hoist above the water on concrete piles. Yet despite the constant flow of traffic across the flyover, they are essentially alone, separated from all those lives by speed and steel and combustion. She thinks that it is odd that it is possible to be this close to so many people, but to feel completely separated from them, alone even.

Except for the boy, of course. In the darkness, unseen, he is asking what she has in mind, what her plan is, and she smiles invisible smiles, forcing down pride and excitement.

“It’s better than C&A, anyway. And there’s no danger of us getting caught. Nor of anyone getting hurt.”

Out in the lake is a jump ramp, a boon to the town’s water skiers. Alice has often seen them on weekend days through the window of her parents’ car. She first noticed them a few years before, when she was being driven to see her grandmother in the hospital, during the weeks of illness before she died. Ever since, Alice has been fascinated by the men and their boats, their wet suits and skis and pointlessness. Every weekend, from thirteen until she left school, she would be driven past them, violin across her knees, and she would stare and wonder why they were there, how they came to the decision to spend their free time like that, why they were allowed to defy the gravity that sucked at her feet.

“That. We blow up that.”

She is pointing at the ramp, some 30 metres away across the water. Phillip hesitates, complaining that he cannot throw the grenade that far. Alice appeals to Hal, calling him out to see off the boy with feet of clay, the man who lives with his mother. Her frustration dissolves, almost as soon as it has risen, in the paleness of his outstretched hand, palm upwards. Alice passes the grenade to him, surprised at the relief of its absent weight. Hal takes the weapon without a word, the darkness cloaking his smile. He is smiling. She knows this without seeing. There is that sparkle again, the twist of his mouth, invisible, the devilry, the child. It is elemental.

Hidden, he removes first one band, then the second, from the lever. He pushes the black scrunchies into her palm, firmly but without aggression. Her fingers close over their softness, forming a fist, too tight for its purpose. Her jaw is set, clenched like the lever on a grenade, and its tension surprises her.

“That?”

She knows that his left arm is extended, his finger trailing in the dank air towards the black fuzziness in the water. She nods, knowing he does not need to see her to know.

When it comes, she is surprised by the movement, the violent displacement of his arcing, straining arm, the rushing of cotton and wool against each other, against skin. She believes she can hear the grenade looping through the air; she can almost see it, even though she knows this to be impossible, imagined. Only the sound of metal parting water in the distance is real, is physical.

They stand at the water’s edge, separate and together, staring at the flat surface. Silently they count, first to seven, then to ten, then twenty, both braced against the blast. The evening’s darkness wraps around them, holding them in its chill. Alice slides her hand into his, and together they stand on the shore, waiting while nothing happens.

- How I love words: a prose poem in praise of cadence

I love words. The way they flavour the things we feel, the things we see, the things that touch us. I love the way that they collaborate, conspire, and conjoin: the shapes they make in the mouth. I have my favourites, of course. Words whose geometry and chemistry give me secret pleasure in their repetition. Cadence. The way it hangs, amplifying its meaning in measured resonance. Resonance itself resonates, but verb and noun taste distinct upon the tongue.

I have no knowledge of the hierarchy of nouns and verbs: which is the parent and which the child. No inkling of the relative pre-eminence of action and indolence, of the transient and the immutable. With adjectives and adverbs things are clearer: they are secondary, the supporting actors of elaboration. But nouns and verbs tussle for supremacy in my sentences, playing chicken and egg with my reasoning.

To delve into the richness of allusion that my mother tongue affords, to unwrap each evocative layer from brute communication, prompts questions. Does a Spaniard savour the texture of expression with such gusto? I have no reason to doubt he does. But I am certain that, of all the advantages of my birthright, this shifting, subtle language is the most prized. I love these words, they are my favourites: which are yours?

- Watching Newcastle United

Instead of a family, I have a city. It is as precious to me as an aunt, as timeless as a grandfather. Its shapes and sounds are etched still into those that remain.

A glimpse of its bridges, arcing over that slow stream, fills me with regret, longing; or simply with a nostalgia for something beyond the reach of memory. It is beautiful to me; it is a thing of pride, a site of unquestioning belonging. A marker of specialness.

It is mine and I am its. But I could not live within its walls: its close familiarity would murder me.

- Between

Wrapped today in pageant paper,

tied in ribbon, tied in knots,

a spotlit summer Saturday

of greenery and white.Yet the point between remains,

constant,

simple,

veiled.On other days too, hidden among

photographs,

envelopes,

bustickets;through murmuring tunnels, lost under trees

draped over downs;

between postcard lines sent from tourist towns,

behind rainsmeared windows

on stolen autumn days;

or in the shadows of hazy half-curtain light,

where afternoons embrace evening,

softly;in the distance of absence and between the tears

left on an empty pillow,

and again on their return;

and even in the voice-crack snap of anger,

and the damp-dark patches

beneath long silences.Sometimes an ocean,

sometimes less than skin,

moments between remain,

strong,

unchanged,

within.

- Policy consultancy

I’m a policy wonk by profession and, over the last thirty-odd years, I’ve worked in think tanks, public agencies, and charities, in Whitehall and in local government. I’ve covered a variety of policy areas, but usually with an emphasis on place. My experience extends across the whole waterfront, from research and analysis through policy development and on to strategic influencing. Over the last ten years, I've been using my experience to help a number of clients with policy projects.

If you'd like to discuss opportunties to collaborate, do get in touch.

- The Connection at St Martin in the Fields

I advised The Connection at St Martin in the Fields, a high-profile homelessness charity working with rough sleepers in Westminster, central London. Drawing on my 20+ years experience of pubic affairs, I helped them to develop an influencing strategy so that their unique expertise and insight can contribute to national and local responses to homelessness more widely.

- UK Health Alliance on Climate Change

I worked with the UK Health Alliance on Climate Change, which brings together doctors, nurses and other health professionals to advocate for responses to climate change that protect and promote public health, to develop their influencing work. In particular I provided advice on their lobbying efforts around the Environment Bill 2020, helped to refine their messages and positioning on air quality, and drafted their policy document on food and diet.

- Ramblers

The walking charity Ramblers collected a massive data set on the condition of the country’s public rights of way through their Big Pathway check app. They commissioned me to analyse the data and to draft the final report, The Big Pathwatch: The State of Our Paths, which was published in November 2016 and launched a major public-facing campaign. I also worked with them as the interim Head of their Policy and Advocacy team, helping them to develop a new strand of work around urban walking, including establishing the Britain's Best Walking Neighbourhood Awards.

- New Local

I worked with New Local, a think tank that works to transform public services and unlock community potential. I have helped them with projects, from supporting local authorities directly as they respond to the difficult circumstances they face, to writing research reports on a range of policy issues around places and local services. For example, I helped a consortium of local authorities develop their plans for a bid to Government for a ‘Devolution Deal’, I wrote a short pamphlet on arts funding, and another on how good urban design in new housing developments can improve social and economic outcomes.

- Respublica

I worked with Respublica to help on their Beauty commission, seeking to find policy responses to the dearth of beauty in our towns and cities. I co-wrote the initial pamphlet, A Community Right to Beauty, setting a policy agenda for beauty in the built environment. I also helped them produce a report for Suffolk County Council on the development of a county-wide housing growth strategy.

- World Cities Culture Forum

Working with the consultancy, BOP, I co-wrote the 2015 edition of the triennial report of the World Cities Culture Forum. The Forum is a global alliance of over thirty world cities from San Francisco to Seoul with an interest in harnessing the power of culture to further their urban policy goals.

- Plan International

I worked with Plan International, a global NGO supporting children around the world, to write articles and speeches for their Chief Executive, Ann Brigitte Albrechtsen. These pieces focused on promoting girls’ rights, and appeared in places like the Huffington Post and the WEF Global Agenda site.

- Editorial services

I have gained extensive editing experience during my career in policy and as an author. I have edited everything from policy reports to journal articles to speeches, both in-house and as a consultant. Whether it's a novel or your annual report, I can help make the language sing and the meaning clear. I offer the following editing services (I'm afraid I'm not a proof reader - that is another skillset entirely).

-

Manuscript critique

Primarily for fiction, I offer a high-level assessment of the narrative voice, plot, and character development. -

Comprehensive edit

For both fiction and non-fiction, I offer an edit that addresses structural issues but with close attention to writing style, language and tone of voice. -

Copy edit

Addressing technical flaws in the text, such as spelling, grammar and punctuation and picking up internal inconsistencies and repetition throughout the text. -

Copy writing

Alongside editing, I can also help with drafting text, for articles, speeches, or longer pieces. -

Writing workshops

I deliver training workshops to help your team develop their own writing and editing skills.

If you'd like to make use of these services, get in touch and we can discuss your requirements.

-

- Journal

- Writing myself(2020-08-24)

It was my own fault. I had decided to write my first novel in the first person, so I should not have been surprised when family and friends started to ask pointed questions. You see, the protagonist of Being Someone was not written sympathetically: he is not someone men should aspire to be. And yet, when my brother described the book as ‘brave’, I didn’t quite get his point.

Things started to dawn on me when a friend’s friend apparently told her that she wasn’t sure that she would like me as a person if she were to meet me. When my mother said that she was disappointed in me, I began a short but intense period of denial. James is not me, I would tell anyone who paused long enough to hear it.

Fiction is not autobiography, of course, and even when authors write about what they know, their novels are not transcriptions of their lives. And yet some readers wanted only to uncover the ‘me’ that they assumed was woven into the text.

There is plenty of ‘me’ in Being Someone, of course, but that ‘me’ is not contained in a single character, but spread across everyone that appears within the book, not just the narrator/protagonist. My second novel, The Cursing Stone, was written in the third person, but there is still plenty of ‘me’ in that too, again contained within a set of diverse characters who are nothing like me, except in the very important regard that they are human. How could it be otherwise? The only perspective I have is my own; the only loves, fears, and doubts I have ever felt are mine. Other people can only ever be seen through that lens.

Because making characters means drawing on yourself but also on what you observe in others: the raw material, especially for the fine grain, the patina, is everyone you’ve ever met. When you’re writing a novel about human relationships (aren’t they all?) and you’re perpetually hungry for ever more granularity, every conversation – those you participate in, those you overhear – is legitimate source material. Every haircut, every nose, every pair of shoes or nervous laugh is fair game. A writer observes, for sure; but more than that, a writer listens. If you can’t hear it authentically as you write it - the words and the cadence - then nor will the reader when they read it.

This I knew. Then I started to notice that I was actively mining conversations, exchanges, and interactions for material. Not just observing, noting, what was going on, but mentally writing it into my novel as the exchange was happening. And if the conversation didn’t fully meet the needs of the character or plot, I found myself steering it in ways that would. I stopped doing that, of course, for my own sake as much as my friends: it felt like stealing, but moreover I was disturbed by the idea of fictionalising my life, of turning my relationships into the components of a novel.

Sometimes even observing feels like stealing. But mostly I know it is simply the only way to draw a believable character who will carry the attention of a reader, and behave with sufficient authenticity to make solid the make-believe of my narrative. So while I was not brought up on a remote Scottish island, I was once 20 years old (although not for a very long time) and there is enough of me – and of you – in Fergus Buchanan make his quest for the cursing stone worth following.

- About a cow(2019-03-21)

Inspiration comes from many places. You’re never sure where, or when, or even whether, it’s going to appear, so the trick is to be ready, to be vigilant. But you can go looking for inspiration. Personally, I’m fascinated by places and the stories that emerge from them, so simply being in new places, ready to listen, is sometimes enough.

About seven years ago, I was in the far north west of Iceland. I love Iceland and have been there several times, most often to walk in its sparse, stark landscape. I’d found my way to Isafjordur in the West Fjords because someone on another trip had mentioned a place called Hornstrandir. The walking was supposed to be spectacular, the landscape too. So I’d made it this far, intent upon a recognisance trip ahead of a possible longer trip.

I took a little boat early one morning out of Isafjordur, headed towards Hesteyri, the ghost of the largest settlement on Hornstrandir. Ghost because the whole population had voted to abandon the peninsula in the early 1950s. There is no permanent human habitation and visits are only allowed during the short two months of summer.

Since the abandonment, the landscape has been left to return to its natural condition: with the sheep gone, the orchids have recovered; with the shepherds gone the Arctic Foxes have become bold and playful. It is a truly special place (although the snow still sits on the beaches in July – the merest thought of a February there makes it easy to understand why the people left.)

All of this I knew from the guide book and the internet. But on the boat heading across the great bay, I got talking to the young Icelander who was our guide for the excursion. Her family had lived in Hesteyri, and her grandfather had left with the others in the fifties. He’d had a cow and, once across the bay, that cow wouldn’t milk, so he had taken the beast back across a couple of summers later and, sure enough the cow gave milk.

A couple of years later, that story of a homesick cow became the starting point for my latest novel, Time's Tide. Between that short seaborne conversation and sitting down to start writing in north London, the story had become one of the relationship between a father and son, the guilt of leaving and the powerful pull of place. But its roots run back to a sunny day on the edge of the Arctic and the story of a cow.

- Canna’s Cursing Stone(2016-11-04)

It’s hard to get lost on Canna. At only five miles long and one mile wide, you can pretty much always see the sea, usually from the tops of tumbling cliffs. It’s a good thing because, especially at its western end, the island itself is fairly featureless moorland, a rising and falling strip of grassy undulations reaching out into the western ocean. And aside from a million rabbits, thousands of birds, and hundreds of sheep, it is empty once you leave the clutch of houses that cluster around the natural harbour.